In 1862, the British photographer William Saunders established one of the first photography studios in Shanghai. Locals and travelers alike sat for his camera, and the resulting images allowed many people to see themselves in a new form that cost much less than the traditional genre of painted portraits. Although they were originally albumen silver prints, they featured color, like paintings: Saunders likely hand-painted them himself; his studio, which hired Chinese artisans, was actually responsible for producing the first hand-colored photographs of China.

The first public exhibition devoted to his work is now on view at the China Exchange in London as part of Asian Art in London. Curated by Stacey Lambrow, the more than 35 prints arrive from the Stephan Loewentheil Historical Photography of China Collectionand capture the faces and costumes of Shanghai during the late Qing dynasty, all framed by the conventional trappings of European portraiture.

Originally an engineer, Saunders had first travelled to China in 1860, when he was about 28 years old. Upon returning to Great Britain, he studied photography and then returned east with his gear to settle down and set up shop. His photography studio, according to Lambrow, was Shanghai’s most successful. It helped that it stood near the famous, Westerner-owned Astor House Hotel(which, previously called the Pujiang Hotel, had then just received its English name), situated at the center of social activity by the city’s waterfront. Saunders opened his business at a period when foreign shops in general were emerging in that neighborhood, developing the Bund into a commercial, modernizing hub.

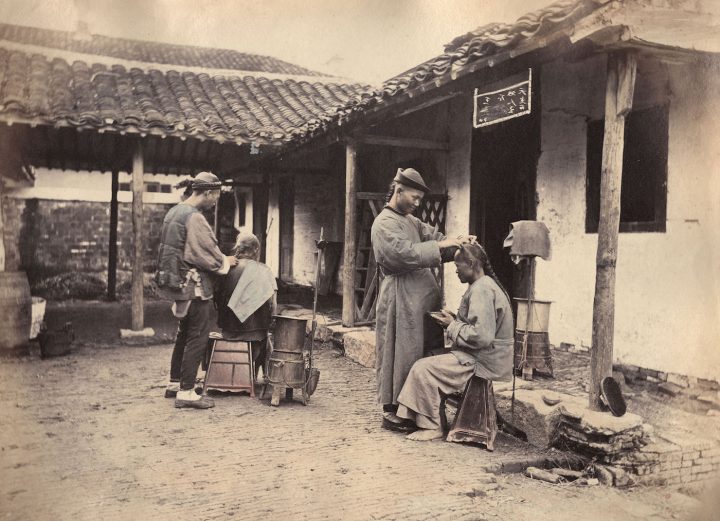

Many of his photographs capture these changes occurring in the city, discernible in hairstyles, clothing, and props. Some of his female sitters wear traditional silk dresses and have their hair in elaborate updos but sit in Western-style chairs, with their feet unbound and in slippers. Other women still have their feet wrapped tightly, such as a pair who freeze for the camera with parasols — a highly fashionable accessory at the time. Another photograph, taken outside the studio, shows barbers at work: as one shaves his customer, another braids a man’s hair in a queue — the style imposed by the Manchus during the Qing Dynasty that had ousted the Han topknot.

Saunders certainly worked with the eye of a Westerner and with the notion of presenting his works to an audience beyond China. The portraits in this exhibition arrive from Sketches of Chinese Life and Character Studies, a portfolio he published that illustrated journals and books all over the world later replicated, well into the 20th century, according to Lambrow. Many of these would have fascinated foreigners, such as his picture of a young man who sold colorful feather dusters — typically on the street, but here displaced in the quiet, isolated setting of the studio. Another documents Chinese theater actors in traditional masks and ornate silk costumes, posing rigidly as if for a yearbook class portrait.

Saunders’s studio closed around 1887. His successful enterprise benefited him immensely, but he also created jobs for Shanghai residents, employing them in his studio as well as assigning them to travel across the nation to take photographs. More broadly, his studio helped boost the presence of photography in the city immensely, and many Chinese artisans soon took on jobs as colorists for other emerging photographers or even became established photographers themselves.

Life in Qing Dynasty Shanghai: The Photographs of William Saunderscontinues at the China Exchange (32a Gerrard Street, London, United Kingdom) as part of Asian Art in London through November 12.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario